Mission-, Vision-, and Strategy Statements – What They Are and How To Craft Them

Many executives thrash about with mission- and vision statements. Unfortunately, most of those turn out to be a muddled stew of values, goals, purposes, philosophies, beliefs, aspirations, strategies, and descriptions. This article aims to clarify such statements and help you craft your own.

We humans need direction and alignment. Without it, we don't know where to go and as we anyway move, our combined effort may be scattered in such a way that it doesn't yield any desired results. One common tool to define and communicate the direction of a company is the usage of written company statements. This article is a summary based on the amazing work of David J. Collis, Michael G. Rukstad, Jim Collins, and Jerry I. Porras. It is part of my MBA series where I summarize what I've learned during my MBA studies.

Contents

Many executives thrash about with mission statements and vision statements. Unfortunately, most of those statements turn out to be a muddled stew of values, goals, purposes, philosophies, beliefs, aspirations, norms, strategies, practices, and descriptions. They are usually a boring, confusing, structurally unsound stream of words that evoke the response "True, but who cares?" or are so general that no particular emotion is evoked.

The Power of Company Statements

Companies that enjoy enduring success have core values and a core purpose that remain fixed while their business strategies and practices endlessly adapt to a changing world. Evidence shows that putting a clearly defined purpose, values, and strategies at the heart of your company yields better results – from financial performance to employee happiness. Company statements capture the essence of just that. Although no general consensus exists in the analytical segmentation of company statements, they are usually structured as Mission & Values (or Purpose) > Vision > Strategy.

Mission statements capture the core purpose of a company's reason to exist and to deliver value to the world. It may, but not necessarily, also define what a company stands for, i.e. the core values a company seeks to represent. A company's core mission and values stand the test of time. The environment will unquestionably change, but a company's core mission and values – when done well – should not. An example:

"Our mission is to organize the world’s information and make it universally accessible and useful."

Google's mission statement is generic enough to allow full flexibility in the manifestation of that mission (e.g. what products or services to offer to whom) yet provide a concrete direction for the company going forward.

Vision statements define what the company seeks to achieve in the mid-future (e.g. 5 to 30 years, depending on the industry) in order to fulfill its mission. A vision statement should be ambitious yet reachable, provoking yet engaging, and deliver a clear picture of where to aim at. It captures what we aspire to become, to achieve, to create – something that will require significant change and progress to attain. To further use Google's example:

"Our vision is to provide access to the world’s information in one click."

The company’s current nature of business is a direct manifestation of this vision statement. For instance, Google’s most popular product is its search engine service which enables people to easily access information from around the world with just a few clicks or presses.

Value statements communicate fundamental and enduringly important principles that drive an organization's way to operate and function. To further illustrate this, I picked a few examples of Google's written values:

"Focus on the user, all else will follow."

"You can be serious without a suit."

"You can make money without doing evil."

Strategy statements capture the essence of a strategy's objective, scope, and advantage so to provide the required direction and alignment to the committed strategy. We'll dive into a detailed example further below.

The sections below are based on two reputable publications that go into more detail about why and how to craft compelling mission, vision, and strategy statements.

Building Your Company's Vision

The following section is based on the article by Jim Collins and Jerry I. Porras where the authors outline their vision framework that helps to discover and define a company's mission and vision.

The fundamental dynamic of visionary companies shall preserve the core and stimulate progress. Truly great companies understand the difference between what should never change and what should be open for change, between what is genuinely sacred and what is not.

Mission

Mission (also referred to as core ideology by Collins and Porras) defines the enduring character of an organization – a consistent identity that transcends product or market life cycles, technological breakthroughs, management fads, and individual leaders. A company’s practices and strategies should change continually; its mission should not. Mission defines a company’s timeless character. It’s the glue that holds the enterprise together even when everything else is up for grabs. The mission is something you discover – by looking inside. It’s not something you can invent, much less fake.

An effective mission has two parts:

- Core values are the handful of guiding principles by which a company navigates. They require no external justification and a company decides for itself what values it holds to be core, largely independent of the current environment, competitive requirements, or management fads. Clearly, then, there is no universally right set of core values.

- Core purpose is an organization’s most fundamental reason for being. It should not be confused with the company’s current product lines or customer segments. Rather, it reflects people’s idealistic motivations for doing the com- pany’s work. It doesn’t just describe the organization’s output or target customers; it captures the soul of the organization.

I think the following excerpt from Dave Packards speech to HP managers sums up the core purpose nicely:

"[... ] Why are we here? I think many people assume, wrongly, that a company exists simply to make money. While this is an important result of a company’s existence, we have to go deeper and find the real reasons for our being. As we investigate this, we inevitably come to the conclusion that a group of people get together and exist as an institution that we call a company so they are able to accomplish something collectively that they could not accomplish separately."

– Dave Packard

Vision

To further proceed in your mission, direction – a vision of the future – is required. What Collins and Porras call envisioned future consists of an audacious 10-to-30-year goal plus vivid descriptions of what it will be like to achieve the goal. The authors found in their research that visionary companies often use bold visions as a powerful way to stimulate progress. All companies have goals. But there is a difference between merely having a goal and becoming committed to a huge, daunting challenge – such as climbing Mount Everest. A truly audacious goal is clear and compelling, serves as a unifying focal point of effort, and acts as a catalyst for team spirit. It has a clear finish line, so the organization can know when it has achieved the goal; people like to shoot for finish lines. It engages people – it reaches out and grabs them. It is tangible, energizing, and highly focused. People get it right away; it takes little or no explanation.

In addition to just an audacious goal, an envisioned future needs a vivid description – that is, a vibrant, engaging, and specific description of what it will be like to achieve the goal. Think of it as translating the vision from words into pictures, of creating an image that people can carry around in their heads. It is a question of painting a picture with your words. Picture painting is essential for making the audacious 10-to-30-year goal tangible in people’s minds.

Actionable Tips to Craft Your Company's Mission and Vision

Collins' and Porras' worked with many executive teams over the years, so their article further provides actionable suggestions to craft your company's mission and vision summarized below.

Core Values

To identify the core values of your own organization, push with relentless honesty to define what values are truly central. If you articulate more than five or six, chances are that you are confusing core values (which do not change) with operating practices, business strategies, or cultural norms (which should be open to change). Remember, the values must stand the test of time. After you’ve drafted a preliminary list of the core values, ask about each one: "If the circumstances changed and penalized us for holding this core value, would we still keep it?". If you can’t honestly answer "yes", then the value is not core and should be dropped from consideration.

Core Purpose

One powerful method for getting at purpose is the five whys. Start with the descriptive statement "We make X products" or "We deliver X services", and then ask, "Why is that important?" five times. After a few whys, you’ll find that you’re getting down to the fundamental purpose of the organization.

Envisioned Future

Identifying core ideology is a discovery process, but setting the envisioned future is a creative process. The authors have found, that some executives make more progress by starting first with the vivid description and backing from there into the audacious goal. This approach involves starting with questions such as, "We’re sitting here in 20 years; what would we love to see?", "What should this company look like?", "What should it feel like to employees?", "What should it have achieved?", "If someone writes an article for a major business magazine about this company in 20 years, what will it say?". It makes no sense to analyze whether an envisioned future is the right one. With a creation, there can be no right answer.

The envisioned future involves such essential questions as "Does it get our juices flowing?", "Do we find it stimulating?", "Does it spur forward momentum?", "Does it get people going?". The envisioned future should be so exciting in its own right that it would continue to keep the organization motivated even if the leaders who set the goal disappeared.

Creating an effective envisioned future requires a certain level of unreasonable confidence and commitment.

Finally, in thinking about the envisioned future, beware of the "We’ve Arrived Syndrome" – a complacent lethargy that arises once an organization has achieved one goal and fails to replace it with another. NASA suffered from that syndrome after the successful moon landings. After you’ve landed on the moon, what do you do for an encore? It's time for a new vision.

Can You Say What Your Strategy Is?

In 2008, David J. Collis and Michael G. Rukstad published an article that's based on asking executives just that question.

Can you summarize your company’s strategy in 35 words or less? If so, would your colleagues put it the same way?

It is Collis' and Rukstad's experience that very few executives can honestly answer these simple questions in the affirmative. And of those that said "yes", the companies that those executives work for are often the most successful in their industry.

Conversely, companies that don’t have a simple and clear statement of strategy are likely to fall into the category of those that have failed to execute their strategy or, worse, those that never even had one. In an astonishing number of organizations, executives, frontline employees, and all those in between are frustrated because no clear strategy exists for the company or its lines of business.

The Value of Rhetoric

The value of rhetoric should not be underestimated. A 35-word statement can have a substantial impact on a company’s success. Words do lead to action. Leaders of firms are mystified when what they thought was a beautifully crafted strategy is never implemented. They assume that the initiatives described in the voluminous documentation that emerges from an annual budget or a strategic-planning process will ensure competitive success. They fail to appreciate the necessity of having a simple, clear, succinct strategy statement that everyone can internalize and use as a guiding light for making difficult choices. A well-understood statement of strategy aligns behavior within the business. It allows everyone in the organization to make individual choices that reinforce one another, rendering everyone exponentially more effective.

Anatomy of a Good Strategy Statement

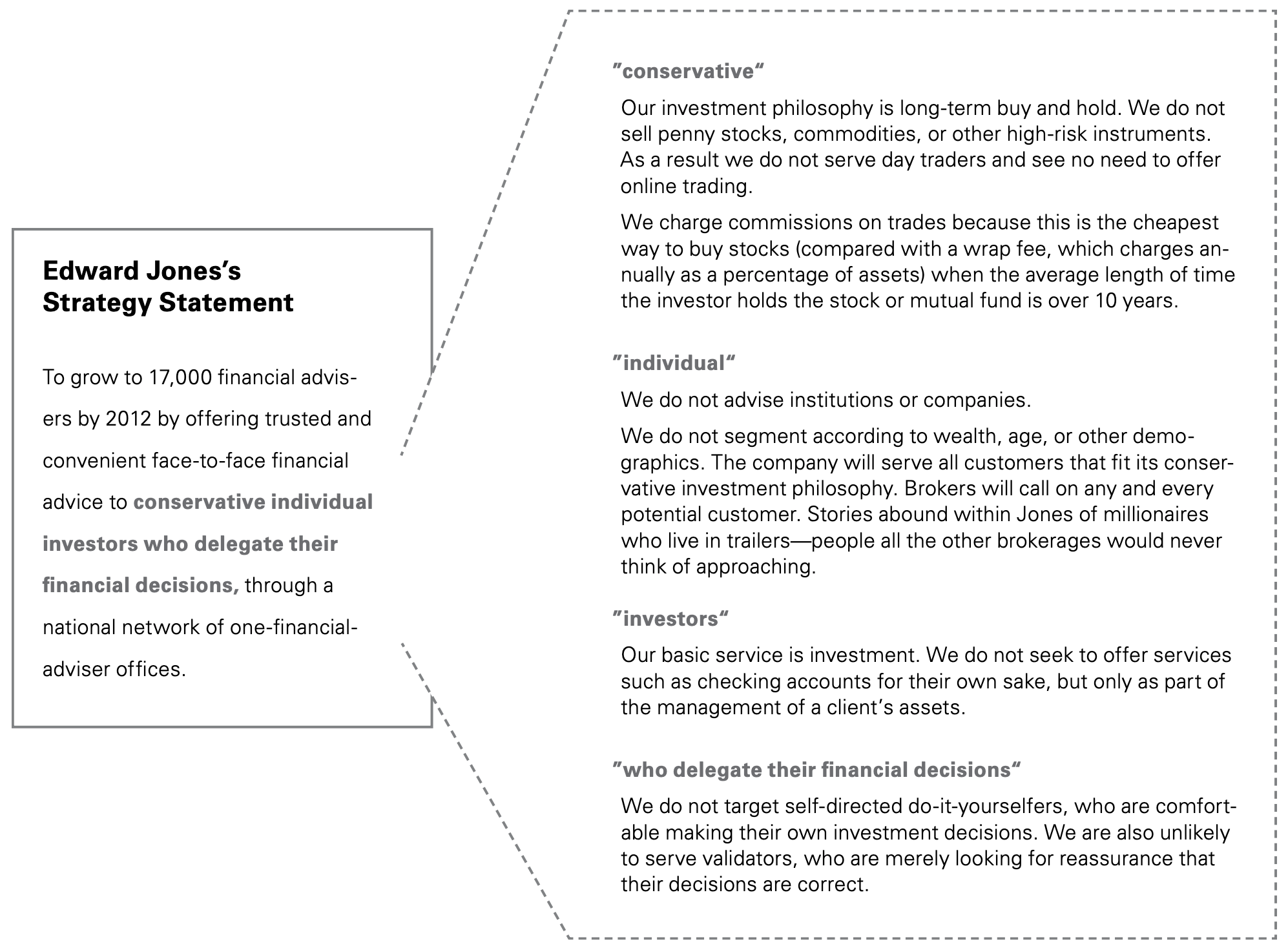

The late Mike Rukstad identified three critical components of a good strategy statement – objective, scope, and advantage – and rightly believed that executives should be forced to be crystal clear about them. An example of Edward Jones' 2008 strategy statement:

To grow to 17,000 financial advisers by 2012 (objective) by offering trusted and convenient face-to-face financial advice (advantage) to conservative individual investors who delegate their financial decisions (scope), through a national network of one-financial-adviser offices (advantage).

Objective

Any strategy statement must begin with a definition of the ends that the strategy is designed to achieve. The definition of the objective should include not only an endpoint but also a time frame for reaching it. The strategic objective should be specific, measurable, and time-bound. It should also be a single goal.

Scope

Since most firms compete in a more or less unbounded landscape, it is also crucial to define the scope, or domain, of the business: the part of the landscape in which the firm will operate. A firm’s scope encompasses three dimensions: customer or offering, geographic location, and vertical integration. Clearly defined boundaries in those areas should make it obvious to managers which activities they should concentrate on and, more important, which they should not do. The scope of an enterprise does not prescribe exactly what should be done within the specified bounds. In fact, it encourages experimentation and initiative. But to ensure that the borders are clear to all employees, the scope should specify where the firm or business will not go.

Advantage

What your business will do differently from or better than others defines the all-important means by which you will achieve your stated objective. It contains a value proposition that explains why the targeted customer should buy your product above all the alternatives and a description of how internal activities must be aligned so that only your firm can deliver that value proposition. This is where the strategy statement draws from Porter’s definition of strategy as making consistent choices about the configuration of the firm’s activities, i.e. to achieve "fit" between its activities. Clarity about what makes the firm distinctive is what most helps employees understand how they can contribute to the successful execution of its strategy. Given that a sustainable competitive advantage is the essence of strategy, it should be no surprise that advantage is the most critical aspect of a strategy statement. Furthermore, any strategy statement that cannot explain why customers should buy your product or service is doomed to failure.

Defining the objective, scope, and advantage requires trade-offs. If a firm pursues growth or size, profitability will take a backseat. If it chooses to serve institutional clients, it might ignore retail customers. If it derives its competitive advantage from scale economies, it will not be able to accommodate idiosyncratic customer needs.

Developing a Strategy Statement

Firms in the same business often have the same mission. (Don’t all insurance companies aspire to provide financial security to their customers?) They may also have the same values. They might even share a vision: an indeterminate future goal such as being the “recognized leader in the insurance field.” However, it is unlikely that even two companies in the same business will have the same strategic objective. Indeed, if your firm’s strategy can be applied to any other firm, you don’t have a very good one.

How, then, should a firm go about crafting its strategy statement? Obviously, the first step is to create a great strategy, which requires careful evaluation of the industry landscape. This includes segmenting customers and identifying unique ways of delivering value to the ones the firm targets. It also calls for an analysis of competitors’ current strategies and a prediction of how they might change. The key is to find the sweet spot where the firm’s capabilities and customers’ needs align in a way that competitors cannot match.

The process of developing the strategy and then crafting the statement that captures its essence in a readily communicable manner should involve employees in all parts of the company and at all levels of the hierarchy. The wording of the strategy statement should be worked through in painstaking detail. In fact, that can be the most powerful part of the strategy development process. It is usually in heated discussions over the choice of a single word that a strategy is crystallized and executives truly understand what it will involve.

The end result should be a brief statement that reflects the three elements of an effective strategy. It should be accompanied by detailed annotations that elucidate the strategy’s nuances (to preempt any possible misreading) and spell out its implications.

Cascading the statement throughout the organization, so that each level of management will be the teacher for the level below, becomes the starting point for incorporating strategy into everyone’s behavior. The strategy will really have traction only when executives can be confident that the actions of empowered frontline employees will be guided by the same principles that they themselves follow.

Thank you for reading this far and I hope this article is useful to you. Be sure that mission-, vision-, and strategy statements alone don't provide silver bullets to solve a company's direction- and alignment problems, but putting in the thought, clarity, and discussions required to craft such a statement is a profitable exercise that can yield great results further into the future. Take care!

– Dominik

Sources