The Need For Strategy In a Dynamic World

Having a clear strategy is now more important than ever. This article outlines the groundwork – most famously by Michael E. Porter – for strategy as thought in many MBA studies as well as a scientific framework to shape it.

This article is based on the foundational work of Michael E. Porter to define what strategy is and what strategy is not. It's the basic of almost any MBA curriculum and an interesting read. We'll furthermore explore an approach to shape your strategic planning with scientific methodology – bringing evidence-based order in the otherwise subjective and speculative art of crafting a strategy.

Contents

What Is Strategy?

A summary of Michael E. Porter's article

The Strategy Definition

The answer to the question "What Is Strategy?" is not as easy as it may seem on the surface. Strategy may be misunderstood for simple management tools which won't create long-lasting competitive advantages. Michael Porter provides a differentiated answer in his 1996 article. Yes, the article is almost 30 years old, yet Porter's arguments are still part of the business school curriculum around the world today.

He argues that strategy must create a sustainable competitive advantage (i.e. profitability) with unique strategic positioning by doing different things or things differently than your competitors.

"The essence of strategy is choosing to perform activities differently than your rivals do."

– Michael E. Porter

The myriad activities that go into creating, producing, selling, and delivering a product or service are the basic units of competitive advantage. How a company chooses to perform these activities indicates what strategy it pursues – either implicitly or explicitly.

Generic Strategies

Porter already introduced generic strategies – that is cost leadership, differentiation, and focus – in his 1985 book Competitive Advantage. The generic strategies remain useful to characterize strategic positions at the simplest and broadest level. Let's recap them briefly:

Cost Leadership

In cost leadership, a firm sets out to become the low cost producer in its industry. The sources of cost advantage are varied and depend on the structure of the industry. They may include the pursuit of economies of scale, proprietary technology, preferential access to raw materials and other factors. A low cost producer must find and exploit all sources of cost advantage. If a firm can achieve and sustain overall cost leadership, then it will be an above average performer in its industry, provided it can command prices at or near the industry average.

Differentiation

In a differentiation strategy a firm seeks to be unique in its industry along some dimensions that are widely valued by buyers. It selects one or more attributes that many buyers in an industry perceive as important, and uniquely positions itself to meet those needs. It is rewarded for its uniqueness with a premium price.

Focus

The generic strategy of focus rests on the choice of a narrow competitive scope within an industry. The focuser selects a segment or group of segments in the industry and tailors its strategy to serving them to the exclusion of others. The focus strategy has two variants: In cost focus a firm seeks a cost advantage in its target segment, while in differentiation focus a firm seeks differentiation in its target segment. Both variants of the focus strategy rest on differences between a focuser's target segment and other segments in the industry. The target segments must either have buyers with unusual needs or else the production and delivery system that best serves the target segment must differ from that of other industry segments. Cost focus exploits differences in cost behaviour in some segments, while differentiation focus exploits the special needs of buyers in certain segments.

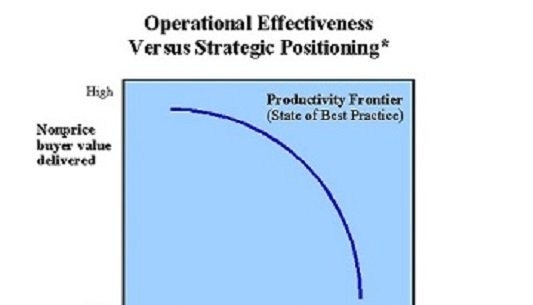

Operational Effectiveness Is Not a Strategy

Porter devotes a large part of his article to operational effectiveness, which – he argues – is often mistaken as strategy. Operational effectiveness means performing these value-producing activities better – that is, cheaper or with higher customer value – than competitors. Operational effectiveness is necessary to compete, yet it will only lead to short-lasting competitive advantages, that can easily be imitated by competitors. This leads to absolute advantages for the consumer, but also mutually destructive competition for the producer.

Porter introduces the concept of the productivity frontier, which illustrates the maximum value a company can deliver at a given cost, given the best available technology, skills, and management techniques. Unless a company has reached the productivity frontier, further improvements in operation effectiveness are possible. Thus, when a company improves its operational effectiveness, it moves toward the frontier. The frontier is constantly shifting outward as new technologies and management approaches are developed and as new inputs become available.

As all competitors in an industry adopt operational effectiveness best practices, the productivity frontier shifts outward, lowering costs and improving value at the same time. And the more benchmarking that companies do, the more competitive convergence you have – that is, the more indistinguishable companies are from one another.

Strategic Positioning

Strategic positioning attempts to achieve sustainable competitive advantage by preserving what is distinctive about a company. It means performing different activities than the competition, or performing similar activities in different ways. It must deliver greater value to customers or create comparable value at a lower cost, or do both.

Creating a Unique and Valuable Position

Strategic positions emerge from three sources, which are not mutually exclusive and often overlap.

Variety-based positioning: Produce a subset of an industry’s products or services. It is based on the choice of product or service varieties rather than customer segments. Thus, for most customers, this type of positioning will only meet a subset of their needs. It is economically feasible only when a company can best produce particular products or services using distinctive sets of activities.

Needs-based positioning: Serves most or all the needs of a particular group of customers. It is based on targeting a segment of customers. It arises when there are a group of customers with differing needs, and when a tailored set of activities can serve those needs best.

Access-based positioning: Segmenting customers who are accessible in different ways. Although their needs are similar to those of other customers, the best configuration of activities to reach them is different. Access can be a function of customer geography or customer scale or of anything that requires a different set of activities to reach customers in the best way. Rural versus urban-based customers is one frequent example of access driving differences in activities.

The Need for Trade-Offs

Some competitive activities are incompatible. Thus, gains in one area can only be achieved at the expense of another area. It's therefore imperative to define what not to do instead of trying to hold different strategic positions at the same time. A strategic position is not sustainable unless there are trade-offs with other positions.

"Trade-offs are essential to strategy. They create the need for choice and purposefully limit what a company offers."

– Michael E. Porter

Simply put, a trade-off means that more of one thing necessitates less of another. An airline can choose to serve meals – adding cost and slowing turnaround time at the gate – or it can choose not to, but it cannot do both without bearing major inefficiencies. Trade-offs arise for three reasons:

- Inconsistencies in image or reputation: A company known for delivering one kind of value may lack credibility and confuse customers if it delivers another kind of value or attempts to deliver two inconsistent things at the same time.

- Based on activities: Different positions require different product configurations, different equipment, different employee behavior, different skills, and different management systems. Strengthening one set of activities requires – given finite resources – weakening another.

- Internal limits: By clearly choosing to compete in one way and not another, senior management makes organizational priorities clear. Companies that try to be all things to all customers risk confusion in day-to-day operations as employees need to make decisions without a clear framework. Internal limits are important to function efficiently and they do impose trade-offs.

Creating "Fit" Among Activities

Strategic fit among many activities is fundamental not only to competitive advantage but also to the sustainability of that advantage. It is harder for a rival to match an array of interlocked activities than it is merely to imitate a particular sales-force approach, match a process technology, or replicate a set of product features.

"Fit locks out imitators by creating a chain that is as strong as its strongest link."

– Michael E. Porter

Positioning choices determine not only which activities a company will perform and how it will configure individual activities but also how activities relate to one another. While operational effectiveness focuses on individual activities, strategy concentrates on combining activities. Competitive advantage stems from the activities of the entire system. There are three types of fit, which are not mutually exclusive:

First-order fit is simple consistency between each activity (e.g. function) and the overall strategy. Consistency ensures that the competitive advantages of activities cumulate and do not erode or cancel themselves out. Further, consistency makes it easier to communicate the strategy to customers, employees, and shareholders and improves implementation through single-mindedness in the corporation.

Second-order fit occurs when activities are reinforcing such as multiple marketing activities reinforcing the same message stronger than any activity in isolation could.

Third-order fit goes beyond activity reinforcement to what Porter refers to as optimization of effort. Coordination and information exchange across activities to eliminate redundancy and minimize wasted effort are the most basic types of effort optimization. But there are higher levels as well. Product design choices, for example, can eliminate the need for after-sales service or make it possible for customers to perform service activities themselves.

The fit among activities substantially reduces cost or increases differentiation. Moreover, according to Porter, companies should think in terms of themes that pervade many activities (e.g. low cost) instead of specifying individual strengths, core competencies, or critical resources, as strengths cut across many functions, and one strength blends into others.

Thus, strategy can also be defined as creating fit among a company’s activities as the success of a strategy depends on doing many things well – not just a few – and integrating among them. If there is no fit among activities, there is no distinctive strategy and little sustainability of any competitive advantage.

Bringing Science to the Art of Strategy

A summary of A.G. Lafley's, Roger L. Martin's, Jan W. Rivkin's, and Nicolaj Siggelkow's article

After having a clear definition what strategy is and what strategy isn't, let's dive into making the process of strategy formation – or strategic planning as Lafley et. al. call it – more scientific.

Most Strategic Planning Is Not Scientific

For all its emphasis on data and number crunching, conventional strategic planning is not actually scientific. Yes, the scientific method is marked by rigorous analysis, and conventional strategic planning has plenty of that. But also integral to the scientific method are the creation of novel hypotheses and the careful generation of custom-tailored tests of those hypotheses – two elements that conventional strategic planning typically lacks.

Bringing Science to Strategic Planning

To produce novel strategies, teams need to adopt a step-by-step process in which creative thinking yields possibilities and rigorous analysis tests them. They should ask what must be true for a given possibility to succeed – and explore whether those conditions hold. The decision is then straightforward: Choose the possibility with the fewest barriers to success.

The seven-step approach developed by the authors adapts the scientific method to the needs of business strategy. Triggered by the emergence of a strategic challenge or opportunity, it starts with the formulation of well-articulated hypotheses – what the authors term possibilities. It then asks what would have to be true about the world for each possibility to be supported. Only then does it unleash analysts to determine which of the possibilities is most likely to succeed. In this way, the seven-step approach takes the strategy-making process from the merely rigorous (or unrealistically creative) to the truly scientific.

Seven Steps to Strategy Making

Applying creativity to a scientifically rigorous process enables teams to generate novel strategies and to pinpoint the one most likely to succeed. The approach works as follows:

- Frame a choice: Convert your issue into at least two mutually exclusive options that might resolve it.

- Generate possibilities: Broaden your list of options to ensure an inclusive range of possibilities. Constructing strategic possibilities, especially ones that are genuinely new, is the ultimate creative act in business.

- Specify conditions: For each possibility, describe what must be true for it to be strategically sound.

- Identify barriers: Determine which conditions are least likely to hold true.

- Design tests: For each key barrier condition, devise a test you deem valid and sufficient to generate commitment.

- Conduct the tests: Start with the tests for the barrier conditions in which you have the least confidence.

- Make your choice: Review your key conditions in light of your test results in order to reach a decision.

Assessing The Validity Of a Strategic Option

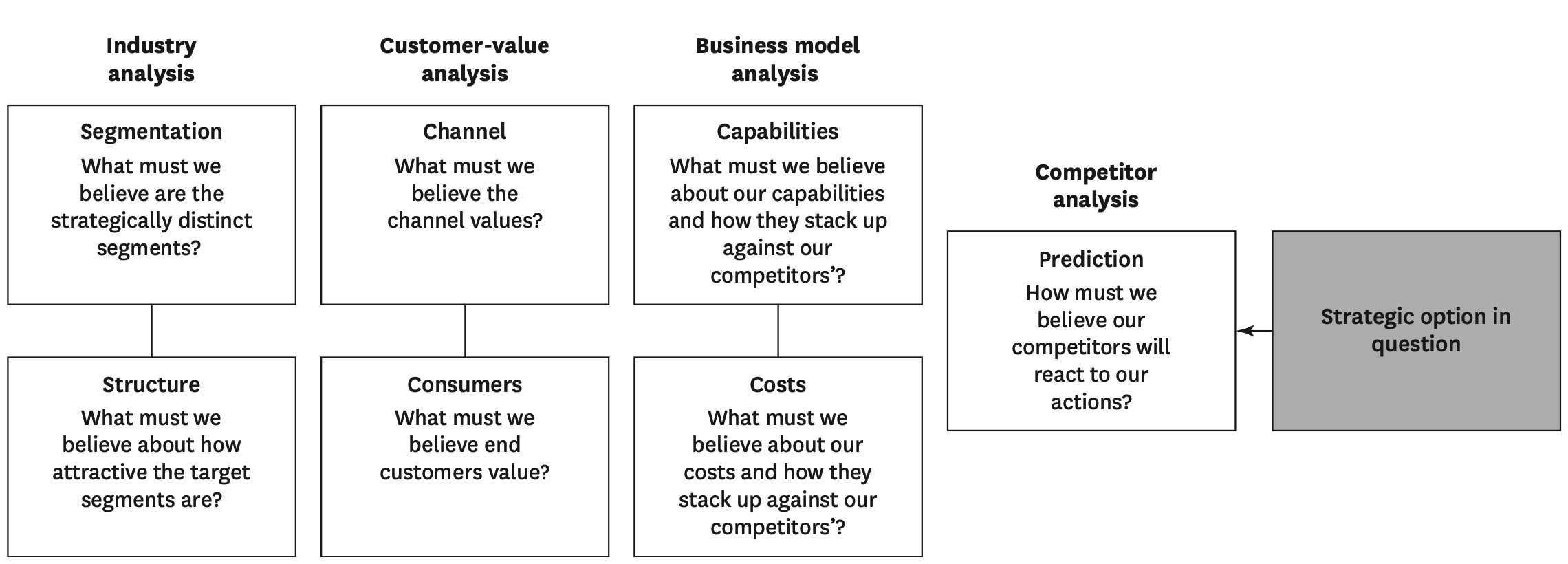

Once you've stated all your options, specify what must be true for each to succeed. The diagram below provides a framework for surfacing the necessary conditions; in effect, you are reverse engineering your choice. Ask "In order to pursue this option successfully, what conditions would we have to believe existed or could be created?" for each of the boxes below:

When done correctly, you will have the scientific evidence to strengthen your strategic decision-making.

Mindset Shift Required

Laid out neatly on paper, the possibilities-based approach sounds easy. But many managers struggle with it – not because the mechanics are hard, but because the approach requires at least three fundamental shifts in mindset.

First, in the early steps, they must avoid asking “What should we do?” and instead ask “What might we do?” Managers, especially those who pride themselves on being decisive, jump naturally to the former question and get restless when tackling the latter.

Second, in the middle steps, managers must shift from asking “What do I believe?” to asking “What would I have to believe?” This requires a manager to imagine that each possibility, including ones he does not like, is a great idea, and such a mindset does not come naturally to most people. It’s needed, however, to identify the right tests for a possibility.

Finally, by focusing a team on pinpointing the critical conditions and tests, the possibilities-based approach forces managers to move away from asking “What is the right answer?” and concentrate instead on “What are the right questions? What specifically must we know in order to make a good decision?”.

The possibilities-based approach relies on and fosters a team’s ability to inquire. And genuine inquiry must lie at the heart of any process that aims to be scientific.

Thank you for reading this far. I hope the article serves you well! If you have any inputs, please let me know!

– Dominik

Sources